Whenever the players go to a new location, they will need certain basic information. If the GM fails to give this information, the game can quickly deteriorate into 20 questions.

Here’s an example of the typical back and forth when the GM doesn’t give enough description:

GM: “You go to the castle”Player: “Are there any people around?”GM: “No. The courtyard is empty.”Player: “What’s here?”GM: “Nothing interesting. Everything has been burned up.”Player: “Burned up? Like the castle was attacked?”GM: “It looks like it was burned and pillaged.”Player: “Ok. Where can I go?”GM: “The blacksmith shop is still standing. Also the living quarters seem untouched.”Player: “Ok. Let’s go check out the blacksmith shop.”

This becomes particularly annoying when the players are in a maze or some place where they have to navigate a lot.

A Good Description

There are several key pieces of information that you should expect the players will ask. Just tell them this stuff up front.

- Where are we?

- What do we immediately notice?

- Are there any people, monsters, or important objects here?

- Where can we go from here?

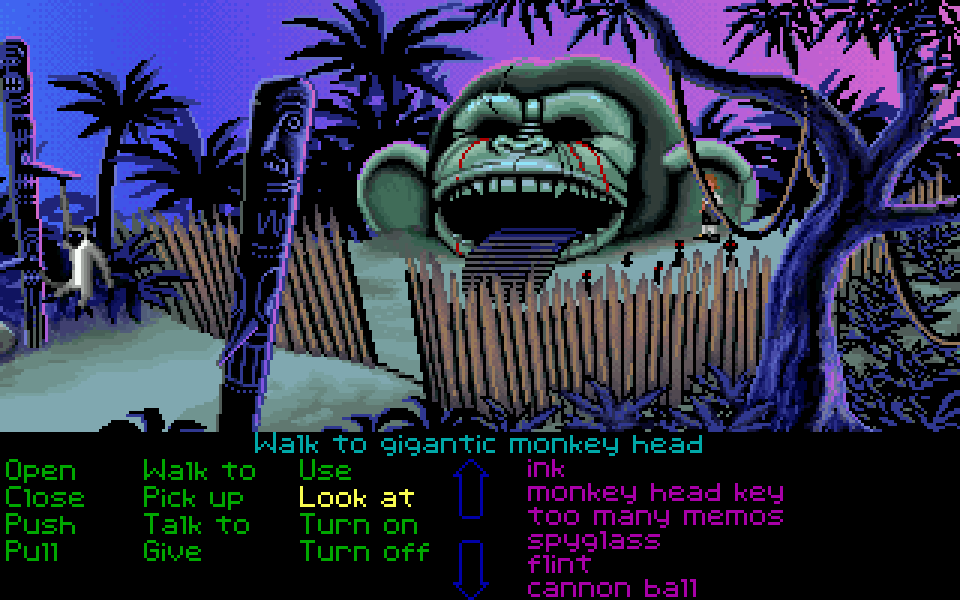

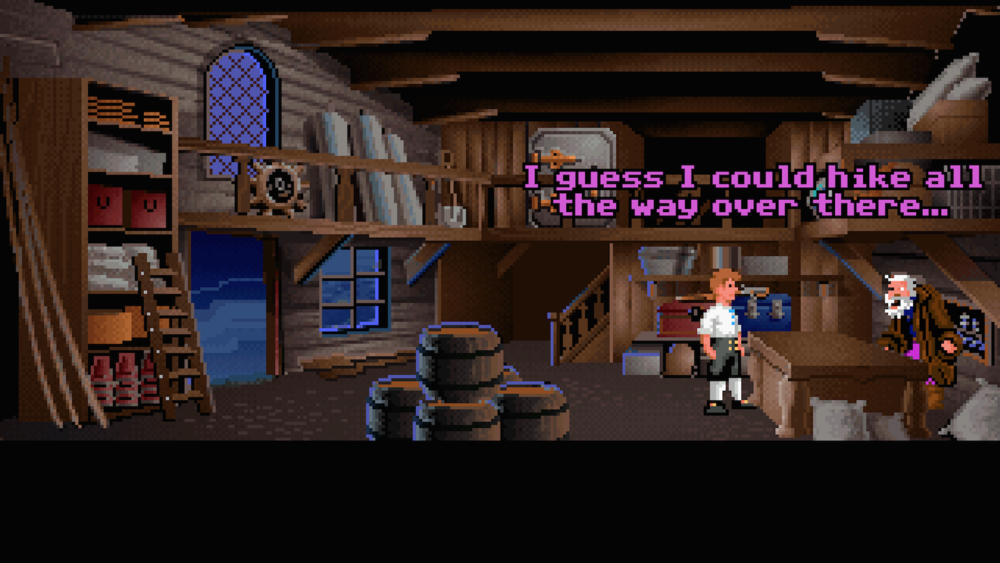

In many ways this hearkens back to the old adventure games like Monkey Island, or the even older text adventure games.

So the bare minimum room description sounds like this:

GM: As you arrive at the castle, you see the gates are wide open. Stepping into the courtyard, you immediately notice that large sections of the castle have been burned down. The courtyard is empty, except for a few broken carts that still smolder from the fire. The only structures still standing are the blacksmith shop, and the living quarters… What do you want to do?

Player: Let’s go check out the blacksmith shop.

As you can see, this feels a lot more natural. The GM has told the players all the important information up front, and the players can quickly decide what they want to do.

GM: You travel for about 2 hours along the road heading east. The clouds begin to gather in the sky, until it’s just a blanket of gray. It’s not quite raining, but every now and then you feel the occasional pinprick of a raindrop on your skin that accentuates the cold. You remember the last time you traveled to the castle it was summer and the sky was a bright blue, now it’s bleak and dreary, on the edge of winter.As you arrive at the castle, you see the gates are wide open and there are no guards posted outside. This is strange considering the last time you were here you had to show papers and check your weapons so the guards would let you through. Now the gate is just wide open. You see a thin trail of smoke coming from inside the castle. There are no signs of life outside.

Player: Does the gate look damaged? Like it was smashed in?

GM: Looking at the gate, you see what appears to be a large crack and a circular imprint on the front. It appears to have been bashed down with a battering ram.

Player: Ok. Let’s go through the gate, but quietly. Stealth… 18.

GM: You step through the gate. Hugging the corner, you stand at the edge of the courtyard. It’s the same square courtyard as before, but instead of a bustling marketplace, you see the bare cobblestone. The buildings here have been ransacked and burned. The stables are a smoldering pile of ash, and only the hitching posts remain out front. There are a few abandoned carts strewn about. Shattered lumber and torn cloth are the only remnants of what used to be multicolored fruit stands–

Player: Oh no! Stimpy the fruit vendor!

GM (continuing): A stream of water trickles from the open rafters and fizzles on the embers. A gentle breeze blows the flag bearing the Stark family crest. It is torn and dangles from one corner, almost touching the ground. To your left you see the blacksmith shop is still standing. To your right, the living quarters are still intact. What do you want to do?

Player: Do I see anyone watching from the windows? Perception… 21.

GM: You don’t see anyone around. No eyes in the windows. No signs of life.

Player: I’d like to walk up to the flag and take it down from where it’s hanging. I fold it up and put it in the bag of holding.

Here the GM has put in more effort to set the mood and make the world feel real. As a consequence, the player’s behavior is more appropriate to the setting. The players sense danger before they enter and decide to make a stealth check. They are constantly worried about someone watching their actions. The cloudy sky and smoldering ruins give a sense of dread. The contrast with the lively atmosphere of the past makes it personal to the players, and one player even gasps when she realizes her favorite NPC is probably dead. Upon entering, the player’s first action is not to go to the blacksmith shop, but instead to pay their respects to the fallen house of Stark. The players are more immersed in this world and feel an emotional connection.

Of course you don’t have to go all out describing every location in emotionally satisfying detail. But it’s good to practice this kind of thing so when you want to set the mood you can do it without too much difficulty.

More Examples

Here are some other examples of room descriptions.

A Maze

GM: You walk through the sewers until you come to a junction. There is a pool of water here with a dead rat in it.You can go north, east, or west.

Player: We go west.

GM: Water splashes at your feet as you walk through the tunnel. You come to another junction. No distinguishing features. You can go north or south.

Player: We go north.

GM: *Splash* *Splash* You come to another junction. You can go east or west.

Player: We go east.

GM: The tunnel curves to the right until you come to another junction. There is a pool of water with a dead rat in it–

Player: Damn! We’ve gone in a circle!

GM (continuing): You can go north, east, or west.

Notice the GM decided to give the players cardinal directions (north, east, south, west) to make it easy for the players to navigate. The GM gave the players a curving tunnel, but made sure to give the players a landmark. This allowed the players to know when they had gone in a circle. A maze is an interesting challenge, but I find that players get bored if the maze is too large, so use them sparingly. It may be just as effective to let the players roll a survival check and say “you manage to navigate the maze, but you get lost once or twice so it takes you a couple hours.”

A Shop

GM: You enter the blacksmith shop and see a large glowing forge at the back of the room. There is no other source of light. The silhouette of a husky Dwarven figure is hunched over an anvil, swinging a small hammer *tink* *tink*. On the walls you see finely crafted armor shimmering in blues and golds, the work of a true craftsman. By contrast the room itself is quite bare, made of unpainted wood beams and rafters. A small silver bell rests on the wooden counter in front of you.

Player: I ring the bell

GM: *Ding* “Just a minute! I’m workin!”

Player: I’ll take a look at the armor.

GM: There’s a beautifully crafted gold chest-plate with intricate markings chiseled into the front. They appear to be dwarven runes but you can’t quite make out their meaning. There’s also a matching pair of gold plate pants, and gloves. …

As you’re examining it, you hear a gruff voice behind you: “Aye! I see you’ve found my fire resistant line of armor!” You turn around to see the dwarf that was working the forge is now grinning ear to ear with his hands on his hips in a full belly laugh. His bald head shines in the firelight, but he has a long bright red beard that hangs down to his belt and is actually tucked into his black pants. He has just massive arms that are just about ripping through is orange shirt. He’s quite large for a dwarf, but is still a good foot-and-a-half shorter than you. He extends one beefy arm in your direction, and looking up at you says “Hello lad! I’m Sammy the blacksmith! Now what can I do for ya?”

Notice that the GM gave enough description up front to set the mood and give the players something to interact with. The players could either call out to the blacksmith or ring the bell. When they do, the blacksmith doesn’t respond immediately. This gives a sense of liveness to the world – that there are other things happening in the world when the players are not around. The players choose to look around the room while waiting for the blacksmith, so now the GM can go into more detail about the armor. This is a desirable kind of back-and-forth between the players and the GM. The players feel like they are interacting with the world, and it responds. But the player’s don’t feel like they are playing 20 questions.

Now the blacksmith interrupts the players while they are looking at the armor. This leads into a character description. Character descriptions are another topic entirely, but I want to show how most of the NPC’s personality was actually conveyed through the description of his workplace, before the GM even described his physical appearance. The shop is bare except for the finely crafted armor. This tells players that Sammy is very proud of his work, and doesn’t waste time with the inconsequential. Sammy continues working when a customer walks in. This tells players he is more interested in his craft than the money from another customer. They will probably get very good armor from Sammy, but he will not part with it unless he is paid what it is worth. Sammy is clearly a no BS kind of guy, so they shouldn’t try to haggle too much. He may be willing to offer a discount if he knows his armor is going to someone who truly appreciates it and is using it for a noble cause. The GM had all this in the back of his mind when he started describing the shop. He gave the players a description that would convey Sammy’s personality naturally through the description of his environment.

And players love an interesting NPC 🙂

Conclusion

Learning how to give good narrative descriptions can be quite a challenge, but it’s really rewarding to see your players get immersed in the world.

If you want more examples, try playing the old text-based adventure games. They do a good job of giving the minimum amount of information so the player can make decisions. You can play some here: http://textadventures.